Who went

Humble people could only afford a passage to Virginia by becoming indentured, but being already in custody and sentenced radically simplified your options. In 1700, for example, a senior criminal judge, gave a boy of about fifteen, James Hall, who was under sentence of death in Glasgow tolbooth for "thieving and pickery," the alternative of transportation to Virginia. Hall accepted.

Humble people could only afford a passage to Virginia by becoming indentured, but being already in custody and sentenced radically simplified your options. In 1700, for example, a senior criminal judge, gave a boy of about fifteen, James Hall, who was under sentence of death in Glasgow tolbooth for "thieving and pickery," the alternative of transportation to Virginia. Hall accepted.

A famine from 1696 to 1700 killed up to 15% of the population. James Chapman, sentenced to death in 1699 for stealing food for his family, appealed for banishment to America. He was whipped and put at Perth on the next appropriate ship. There were few volunteer indentured emigrants, however, and some refused to stay transported. Deportees Thomas Anderson and John Weir, were rearrested in Scotland in 1700.

People knew how indentured servants were treated. An English bondswoman in Maryland reported in 1756 that she was half-naked, poorly fed, "toiling almost Day and Night—with only this comfort that you Bitch you do not halfe enough, and then tied up and whipp'd to that Degree that you'd not serve an Animal."

White indentured field hands became scarce after 1700, and as slaves replaced them, racist attitudes strengthened. Southern colonies legislated against flogging white people naked, which meant they had been so flogged. Man or woman, you needed a strong stomach to volunteer as an unskilled indentured labourer in Virginia.

Virginia, with its perpetual labour shortage, offered high prices for indentured servants. Edinburgh ships, some of them wolves in sheep's clothing with names like The Ewe and Lamb, topped up their passenger list for Virginia with mugged and kidnapped people.

Until about 1740, Syndicates and their skippers were bound to pay a heavy fine for any prisoner who escaped before being landed in Virginia. Most Scots prisoners went to Virginia. Immigrant Scots women helped early eighteenth-century Virginia acquire a self-replacing population. Before 1700, the sex ratio and lifestyle ruled that out. And if Virginia suited these Scots, they did well by Virginia. Despite the homesickness, hardship, and misery, some Scots found that their land of exile had turned into a new home. In 1730, looking back over the first three generations of Scots migration to Virginia, Roderick Gordon, a ship's surgeon and from 1729 resident of King and Queen County, Virginia, wrote:

“Pity it is that thousands of my country people should be starving at home, when they may live here in peace and plenty, as a great many who have been transported for a punishment have found pleasure, profit, and ease and would rather undergo any hardship than be forced back on their own country.”

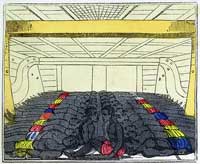

One of the most extraordinary documents of the great era of slavery is that by a tribal chieftain named Zamba. Zamba was a son of a local 'king' who ruled a small community 200 miles up to Congo. The king, Zambola, acquired considerable wealth as a slave dealer, selling to an American captain named Winton. At about the age of 20, in 1800, Zamba himself became king and, having acquired a rudimentary education, determined to extend his horizons by travelling to America with Winton. Winton readily agreed to the suggestion, accommodated Zamba in style on his slave ship - and then, as the ship neared Charleston, imprisoned him and sold him into slavery. Zamba was lucky; he managed to preserve some of his wealth which was invested by his humanitarian owner. He later wrote an account of his life and - since slaves were not allowed to read or write - smuggled his manuscript out with the help of a white friend. It was published in England in 1847.